Go to the nearest window and stare for a moment at an object outside – maybe a car if one is nearby. Now that you’re back, it’s an easy task to recall the color of the car, isn’t it? But how much of the surrounding objects were you aware of? We all feel that we’re conscious of the entire scene, kind of, but would you have even noticed if a tree in your periphery had started magically spinning on its axis?

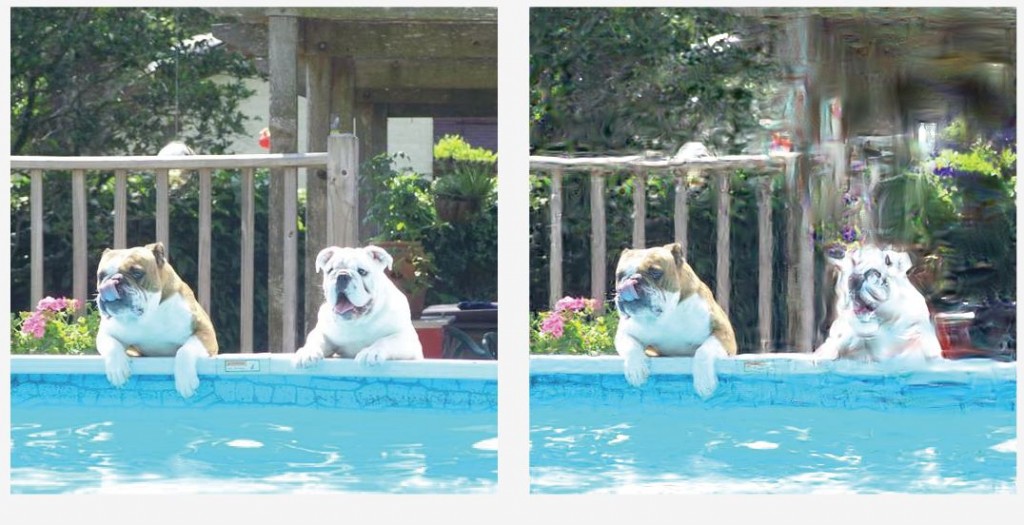

(Freeman and Simoncelli (2011) have shown that, when you are at the right distance and staring at the lefthand dog, both versions of the image look the same to you, even though one version has scrambled much of the periphery)

(Freeman and Simoncelli (2011) have shown that, when you are at the right distance and staring at the lefthand dog, both versions of the image look the same to you, even though one version has scrambled much of the periphery)

In analogous fashion, I personally can drive for miles locked in a daydream, but I don’t crash – is that because some of my consciousness was still managing the driving, or was I purely on autopilot, with my unconscious mind watching the road and control the car for me? This general question of the boundary of our awareness during wakefulness is what I will address today.

It is a question that dominated the recent consciousness science conference, ASSC, which this is the third and final report of (after I talked about the science of hypnosis and magic in the first installment, and the neural symphony of consciousness fading in the second). Many talks throughout the conference aggressively took their theoretical stand on one or other side of this debate, and there was an entire symposium devoted to discussing the question of whether we can be conscious of far more than we can accurately report.

Ned Block chaired this symposium. He is the progenitor of the modern version of the idea that there is a clear distinction between the mere feeling and sensations of consciousness, known as phenomenal consciousness, and the kind of consciousness that we can report on, can behaviorally react to, and so on, which is known as access consciousness. In other words, it’s almost as if we have a far wider conscious border than we generally think we do, partly because there is a very narrow poorly erected fence well within this where consciousness becomes functional for us.

This position has rapidly become very popular, and not just in philosophical circles. For instance, the president of ASSC during the conference, Victor Lamme, entirely subscribes to the theory, and incorporates it into his own prominent neuroscientific theory of consciousness, the Recurrent Processing Model.

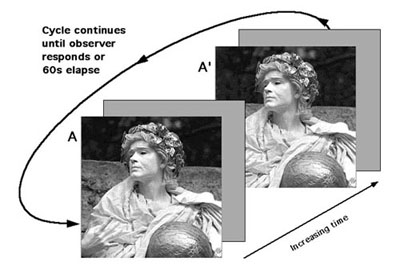

Two key experiments are used to defend the distinction between phenomenal and access consciousness. The first is known as change blindness and is illustrated by the figure below:

Here, the left and right images are alternately shown on the screen, and it takes subjects a surprisingly long time to notice the change (if you haven’t spotted it, look carefully at the wall behind the figure). Ned Block argues that we must be conscious of the whole scene, but only in a phenomenal way, just as you had a sense of the whole scene outside, even if you only centered on the car. Only when the key difference within our more limited access consciousness is noticed can we actually do anything about it, such as proclaim that the wall is different between the two images.

But was detailed information of the whole scene even processed in our brains? A related experiment suggests that it might be.

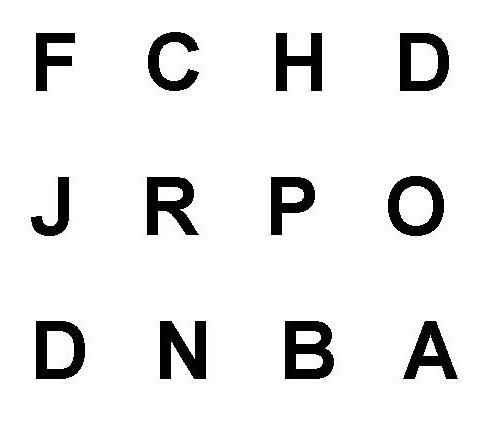

Imagine that for a fraction of a second you see a grid of letters like the following:

Even though it’s present for the briefest of moments, you still may have a sense that you definitely saw all twelve letters, but when asked a second later most people can only accurately report 3-4 letters at random places in the grid, so only a single letter from each row on average. Strikingly, though, if as soon as the grid disappears a cue tells you just to focus on any one of the rows, you can still report 3-4 items from that row, as if somewhere, in your head, there was information about all 12 items. Ned block thinks this test, known as the Sperling Task, demonstrates that our phenomenal consciousness has a superior capacity to our access consciousness – our phenomenal consciousness, he claims, holds information about all 12 items. But our access consciousness only has space for 4 items, so there is an overflow situation, with most of what’s in our phenomenal consciousness not being available for our access consciousness.

The upshot of this is that the form of consciousness that we can report on, can attend to, and so on is tiny – really very limited compared to the much vaster expanse of our phenomenal consciousness. But is this really the case?

I certainly don’t think that these conclusions are the only ones based on these experiments. Let’s instead for the moment assume that phenomenal consciousness doesn’t exist and that instead consciousness is indeed made up of feelings and sensations, but these are all ones that we can talk about, are attending to, take actions in response to and so on. How would we explain the change blindness experiment, where people take ages to spot the wall difference between the two pictures, for example? It’s quite possible that we are aware of the entire scene, but only in the vaguest way, and for a brief moment, with everything that we don’t attend to rapidly fading from consciousness. We point our attention to what’s important about the scene, what we expect from memory to be key features, such as the face, and so don’t attend to, and are not conscious of the change, for many seconds. There is no extra information below what we can report, because what we can’t report is barely processed, rapidly dying data. Even if there were extra information, though – so what? We know from many other experiments that you can have unconscious knowledge, so why not here as well?

As for the experiment with the grid of letters, the Sperling Task, there’s absolutely no evidence that we do indeed have some hidden knowledge superiority for all twelve letters. Instead, all letters are very briefly represented in our visual system and we use attention to boost what we can and place it in consciousness, which happens to be only about 3 or 4 items. This either happens at random locations, without a cue, or on a single row with a cue. But again, even if there was some evidence that all 12 letters were truly still accurately recorded in our brains a few seconds later, so what? If we can only consciously access and recall 4, that’s what we are conscious of a few seconds later. We may at the instant that the letters flash on screen have the weakest conscious sense of all 12 letters, but experiments have shown we aren’t conscious of them as letters, but just as vague objects. It’s as if we have the capacity to store up to 4 items in consciousness, as fully processed items, but we can also smear this conscious (or attentional?) resource more widely, to take in more objects in a more superficial way.

In general, some of the confusion over this conceptual issue rests on the fact that consciousness doesn’t have to equal every snippet of data in our brains – no one really thinks it does. Instead, consciousness seems mainly concerned with the endpoints of analysis, those large structures of data, which means we just can’t help consciously perceive a chair when we see it, instead of all the constituent textures, shapes and colors that comprise it.

One of the most impressive talks of the conference, by Michael Cohen, highlighted just how ludicrous this phenomenal/access consciousness distinction really is. He asked us to imagine some future time when we could surgically alter a man’s brain so that he could still phenomenally perceive color, but this was barred from his access consciousness. What happens when you present the man with an apple? What color does he report it as being? He’ll quickly and confidently say that this is a very strange apple indeed, being entirely grey in color. If the scientist insists that his phenomenal consciousness still perceives it as red, even if he is convinced and tells us it is grey, he’ll laugh at the idiocy of this suggestion – he experiences it as grey, can tell us this, remember the greyness and so on, and so it just makes no sense to claim that there is some other kind of consciousness hidden from him that he has no access to, which differs from his own reportable experiences.

A related important issue for the theory, raised by Sid Kouider in the symposium, is that for it to be a real scientific theory, it needs to be potentially falsifiable. But could we ever devise an experiment that showed that this phenomenal consciousness that we have no clear awareness of, can’t speak about, act on, etc. isn’t actually unconscious after all? What possible benchmark or index could we come up with to potentially prove the non-consciousness of phenomenal consciousness? If we can’t do this, then doesn’t that make the theory meaningless?

The upshot of this is that there is only one kind of consciousness and it really is severely limited in some sense. But there are two reasons for why this isn’t crippling: first, once we’ve consciously learnt some complex skill, our unconscious minds are supreme at running those automated programs, for instance by driving a car while we daydream. Second, we may only be able to be fully conscious of a handful of items, but we can draw on a huge knowledge-base for each of those items, understand them profoundly, and examine how they relate to each other. It is this last conscious process, I believe, that makes humanity such a powerful species, capable of such sparkling insight.

5 comments

Skip to comment form

It appears to me that once again the consciousness community is arguing about what the operational definition of consciousness should be. Please notice that I wrote “should be” rather than “is”. Daniel, it seems like you are taking on stand on “is”. But operational definitions are made by convention and they either prove useful in models or they don’t. So where is a model which incorporates the quantity called consciousness? If one exists is it useful?

Author

Hi DS,

As we’ve discussed in earlier posts, we are not yet at the stage of operational definition, but there are places within the science that are moving toward this, both on a psychological and neuroscientific level.

But the main point I was making here was that one theory doesn’t even make conceptual sense, leaving aside operational definition issues, so should be rejected for those reasons.

Hi Daniel

You wrote that “one theory doesn’t make conceptual sense”. But I don’t see a theory being presented. I see arguments over operational definitions. Theories make prediction based on a model and those predictions can be subject to testing – falsified. But operational definitions can not be falsified. They are either prove useful in the context of a theory or they don’t.

Maybe I am wrong. Maybe there is theory in there somewhere but I don’t see it yet.

Author

Kenny E. Williams writes:

“I was wondering how one’s working memory is/might be connected to either the phenomenal or access consciousness, as you and others might describe it. I know my question might be vague somewhat, but somehow I connect the idea of our working memory within your theme of consciousness,

And, yes, I too have wondered how did I get to work without remembering or perceiving getting off or on the interstate!”

Thanks for this comment, Kenny. And it’s a great question as to the relationship between working memory and consciousness, and how it straddles this theoretical issue. Working memory definitely relates only to access consciousness, not phenomenal consciousness. But if you leave that theoretical debate aside, I think that it all depends on how you define working memory. But you can define it in such a way as that it is the same as the contents of consciousness. I talk about this quite a lot in my consciousness book, The Ravenous Brain, devoting a good part of two chapters to this question. So if you wanted to delve into this question more deeply, perhaps you could have a look there?

Indeed, I am looking forward to reading the book…thanks. I am just delving and diving into Daniel Kahneman’s, Thinking Fast and Slow, and will add the Ravenous Brain to my fall reading list!