This is the second part of my report on the recent consciousness science conference (ASSC) in Brighton, UK. After the first day, where I attended workshops on the science of hypnosis and magic, the four day conference began in earnest.

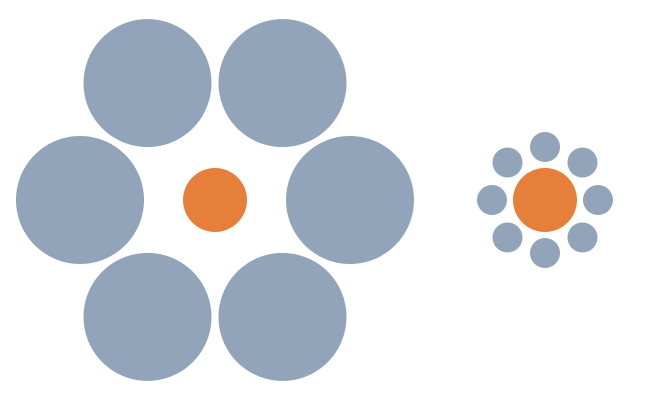

Fascinating piecemeal new details about consciousness were revealed at regular intervals throughout the conference. For instance, have a look at this image below:

Believe it or not, the inner circles on the left and right are the same size (this is known as the Ebbinghaus illusion). Intriguingly, some people are more susceptible to this illusion than others (young children are hardly susceptible to it at all). Geraint Rees’s lab has been looking into why this might be, and has found that those with a larger primary visual cortex have a less intense illusion. Exactly why this is remains unclear, though Rees speculates that it’s as if there is a greater resolving power of more neurons in a larger visual cortex, so less opportunity to get confused in such ways.

Another exciting new feature of consciousness revealed at the conference relates to the question of whether consciousness is an all or nothing affair, or a continuum. Say there is a faint object in front of you – are there only two options: Fully consciously perceiving it, or being completely unconscious of the object? Or, instead, are there many different levels, where you can at times be partially aware of the object? The answer, as Bert Windey and colleagues showed, is that it actually depends on what you are trying to perceive. If it’s a simple feature, such as a colour, then our consciousness works in a more graded fashion, where we can catch weak glimpses of the object at times. But if the feature is something more conceptual and high level, like a number, then the situation is much more as if we are either are conscious of it or we aren’t – there is no in between.

But the highlight of the early part of the conference for me was a fascinating symposium by Gernot Supp, Melanie Boly and Emery Brown, on what happens in the brain when consciousness fades. A common way of studying this is to examine what happens when a general anesthetic drug is administered. The current answer is that the prefrontal cortex at the front of the brain and the thalamus (a central hub in the brain’s network, situated in the middle of the brain) start to sing the same tune: Their rhythms become tightly harmonized in the alpha band (about 10 Hz). Given that alpha waves are linked with relaxation, this is all unsurprising so far. What is more surprising, though, is the mechanism by which this shuts down consciousness. The prefrontal cortex and thalamus are closely linked with consciousness, probably by acting as a general purpose staging area for any specific conscious contents arriving from elsewhere in the brain. In anesthesia, these two key brain areas for consciousness are generating such an intense, harmonious (alpha wave) duet that the rest of the brain is barred from the song, and other cortical areas become isolated. And so those other parts of cortex that give detail to consciousness – managing our senses or memories, for instance – can’t access this consciousness network, and without any specific content to consciousness, there is no consciousness. This cutting edge research highlights the emerging picture of the neuroscience consciousness, where local islands of activity are simply not good enough. Instead, much of the cortex has to collaborate in a global wave of activity for consciousness to occur. If you are interested in learning more about how the brain generates consciousness, you might like to take a look at my upcoming book, The Ravenous Brain.

In the next and final part of my report on the recent ASSC conference, I’ll be discussing the main theoretical debate of the conference: Whether our awareness is far broader than the limited part of our world we can consciously describe.

6 comments

Skip to comment form

I am confused. How, without a operational definition of consciousness, does one ask the question whether it is continuous or discrete in its response to stimuli. Did Bert Windey provide his operational definition? If not then perhaps we should not be concluding that his experiment exposes any of the properties of consciousness.

I saw two equal size orange dots almost immediately upon looking at the images prior to reading your explanation of the experiment. There was approximately a 1 second delay between seeing the dots immediately of different sizes and seeing the dots to be the same size. The transition generated an odd feeling.

“Whether our awareness is far broader than the limited part of our world we can consciously describe.”

I guess that would depend upon your operational definitions of “awareness” and “consciousness”.

Author

Hello again DS, and thanks for commenting.

What the Windey experiment did was tweak the stimuli for each subject so that they were just on the boundary between being reported by the subject as being clearly consciously perceived and being reported as not consciously perceived at all. Then you can explore this boundary for each trial by asking them to rate how conscious they are of the stimuli, on a quite well used scale, called the Perceptual Awareness Scale (a four point scale, starting with “not seen” then “weak glimpse” then “almost clear image” and finally “clear image”). For the colour feature, subjects had a relatively equal distribution of answers across the scale (indicating continuous levels of consciousness), but for the number feature, they tended to answer mainly at the extremes (indicating a more all-or-none situation). One can quibble over definitions of consciousness here, of course, but I think the approach in this experiment is quite reasonable, practical and it produces very intriguing, useful results for consciousness science.

It sounds like you had a pretty odd reaction to the orange dots, with the illusion fading after just a second – is that right? That’s not my experience at all – I can’t help but see the illusion continuously. I wonder if anyone else reading this has a similar reaction to you – if so, please let me know in the comments section!

As for the last point – I’ll at least partially address this in the next article – that was really just a teaser line to tell you what the next one will be about.

My odd reaction to the orange dots was that they sort of appeared to oscillate in size briefly before becoming of equal size.

Hi Daniel,

Great post..I have seen this “illusion” optically numerous times, and I see the two centers as being asymetrcial every time. I must fully look between both objects to eventually sense their circumerential sameness.

I could not post on your third blog, but I was wondering how one’s working memory is/might be connected to either the phenomenal or access consciousness, as you and others might describe it. I know my question might be vague somewhat, but somehow I connect the idea of our working memory within your theme of consciousness,

And, yes, I too have wondered how did I get to work without remembering or perceiving getting off or on the interstate!

Sounds like the conference had much to be conscious of!!

Kenny E. Williams

Author

Thanks for the comment, Kenny.

I think what you describe is the usual reaction to the illusion. The most effective way of revealing the equality of the size of the inner circles is to remove the outer circles for a moment.

I’ll respond to the working memory questions in the other post (did you have any technical issues stopping you posting there? If so, please drop me a line and let me know what they were)

Yes, that makes sense about removing the outer circles; I think I must be, in a roundabout way, doing that as I look between them. On the third post, the comment box would not open for me the other night, but it did on the second posting. I did go back to the third posting later to reread and noticed that it then seemed operational.

By the way, you have a beautiful daughter…enjoy each minute…my daughter just turned 20 yesterday and is away from home much more than she is here,now. We are to give them roots and wings…believe me, providing roots is much more difficult than watching them fly away!